Lutheran Sacred Music in the Heart of Texas

As the nineteenth century turned into the twentieth, the Wendish settlements expanded throughout Central and even North Texas, bringing with it the presence of the LCMS. As the number of Lutheran churches increased and communities grew in numbers and influence and even wealth, there was not only a need to plant more churches but to think toward Lutheran higher education in the state.

In 1891, a few stalwart Lutheran settlers in Austin, the heart and capital of Texas, persuaded the board of missions of the southern district of the LCMS to establish a congregation in the city, with Rev. Hermann Kilian, Jan’s son, serving as mission pastor. Hermann, assisted by other pastors from Lee County as well as his brother Gerhard, would shepherd the small flock for the first year before they were able to call their first pastor. The church would be known as St Paul Lutheran, and an associated school, which taught in both German and English, would require a teacher.

St Paul’s installed a $1200 Hinners pipe organ in 1914, and called Ernst Thuernau as teacher and church musician. Thuernau, although he would stay only a couple of years, developed a reputation as a concert organist, playing recitals around the state before accepting a post in St. Louis. St Paul continued to be served by competent musicians and grew to such an extent that the congregation spearheaded an initiative to establish a Lutheran college nearby.

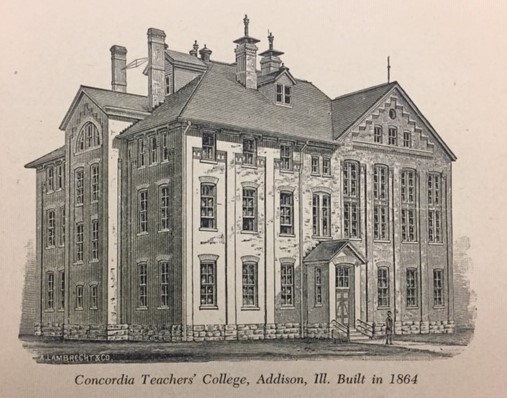

Back to Gerhard Kilian and continuing well into the twentieth century, many of the Texas Lutheran teachers and musicians were trained at the Lutheran seminary in Addison, Illinois, the precursor institution to Concordia Chicago. So it is not surprising that Texas Lutherans would look to the seminary not only for personnel, but also as providing an example when establishing their own college.

Although called a “seminary,” Addison patterned itself after the Gymnasium manner of German education which provided high school boys with a comprehensive classical education in which Latin, Greek, history, and music were among the important subjects studied. Music was such a fundamental part of the curriculum that most of the teachers/professors taught some aspect of music–even the seminary’s president! After what would be the equivalent now of two years of undergraduate studies, the boys could either continue their education (many went to seek ordination), or were eligible to receive calls as teachers. The Addison seminary required all graduates be able to play organ, sing well enough to lead congregational song, and even offered instruction in violin, which was a surprisingly popular instrument for leading singing in the nineteenth century. The Texas Lutherans would look to Addison for inspiration, but Texas is a very different place than Illinois.

At the instigation of St. Paul in Austin, the synod established a new college, called Lutheran Concordia College. The cornerstone of Kilian Hall, named after the revered founder of the LCMS in Texas, was laid on June 27, 1926, to great ceremony and with the accompaniment of “the orchestra of St. Paul’s Lutheran church in Austin, and the band of the Lutheran church at Walburg,” suggesting some of the musical forces these congregations were able to muster, at least for important occasions. The synod paid a portion of the college’s expenses, allowing a historical paper trail starting in 1926, in which the synod approved a “voucher” for a music teacher at the school.37 Structured in the Gymnasium manner consistent with the other colleges, the first faculty included a part-time professor of music—in this case, Ewald F. Wilkening. His main job was as principal, teacher, and musician at St. Paul’s. An organist of some note, Wilkening had been trained in Addison and established a choir and taught musical rudiments at Concordia.

Concordia’s genesis exemplified the challenges unique to Texas. The faculty were relatively young; often seminarians on vicarage were called to teach music for their vicarage year. Space was inadequate for most teaching, and there were complaints about students practicing piano and disturbing the peace! Concordia relied on St. Paul for pastoral and musical guidance through the years, until Concordia finally grew in stature and reputation enough to stand on its own. This transition happened after World War II, and latent friction strained the close ties between the two institutions. Nonetheless, St. Paul’s would continue to call parish teachers and musicians who offered innovative musical leadership. The college fielded choirs which would learn and share sacred music on tour throughout the state. Even as late as 1951, when Concordia adopted a junior college model, the musical facilities were still woefully lacking beyond pianos and a Hammond organ purchased in 1949.

Concordia’s growth after the war would necessitate a building program and evaluating whether enough faculty were serving the school. This corporate introspection resulted in hiring the first full-time music professor.