The Developing Vocation of the Church Musician

Throughout the Lutheran Church in the twentieth century, the role of the parish musician gradually divested from that of the parochial school teacher. Carl Teinert functioned as the first professional “Kantor” in Texas, but only in the twentieth century would that role gradually be refined. There were, during midcentury, stirrings for more from the sacred music vocation. At Trinity Lutheran in Houston, John Behnken had been succeeded by Rev. Oliver Harms (who likewise would become Texas District president and later the LCMS president) who arranged for the church to call Carl Halter in 1937 as “Teacher and Director of Music,” even though he had not graduated yet. The church generously allowed him to finish his degree, and then a graduate degree from Baldwin-Wallace College, where he studied with Albert Riemenschneider. Already a promising scholar, in April 1942, Halter attended a Texas conference of Lutheran pastors and teachers over which national LCMS officials presided and where he offered a lecture dedicated to “Music in the Divine Service,” the first recorded instance of a scholarly presentation on sacred music offered by a Lutheran musician in Texas.

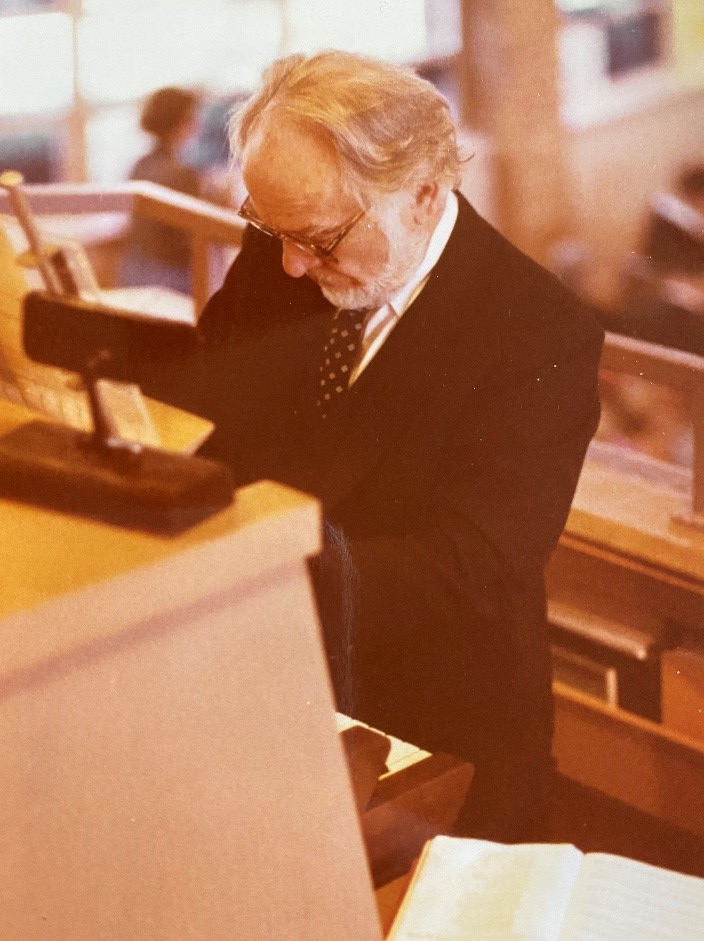

Later that year, Halter would accept a call to Grace Lutheran, River Forest, and eventually to Concordia, River Forest, where he served in various capacities, from music professor to interim president. His 1963 book God and Man in Music, a collection of theological and philosophical essays on church music, likely represents the first instance in the LCMS of a musician publishing theological reflections on church music. During his five-year tenure, Trinity, Houston, had invested in their young schoolteacher and musician, bestowing upon him the title of “Director of Music,” a suggestion that his role was more than that of simply organist, and granting him time to pursue his academic studies.

Herbert Garske succeeded Halter at Trinity in 1943. Garske likewise had been born and confirmed in Chicago, graduating from Concordia, River Forest, and the American Conservatory of Music in Chicago, after which time a call to Buffalo, New York, allowed him to study at the Eastman School of Music. Although his service to Trinity was in both teaching and music ministries, Garske’s musical qualifications were unparalleled in Texas Lutheranism. Rev. Harms must have desired and expected a musician of the highest professional

and musical standards, a musician who had achieved beyond the standard training offered to undergraduates. As they had with Halter, Trinity permitted Garske the liberty to pursue his musical interests and the time to engage more in church music when possible. Due to this generous flexibility of employment, no doubt encouraged by Rev. Harms, in 1949, Garske earned a graduate degree in music from Northwestern University. Indeed, it is likely that Garske was the first LCMS musician with a master’s degree (in this case, two graduate degrees) to serve full time in Texas. Garske left Texas in 1964 to teach at Concordia, Ann Arbor.

Rev. Carl Gaertner, a Texan by birth, was called to Zion Lutheran Church in Dallas 1951. Always interested in and supporting of parish music ministries, he was aware of the professional support Trinity had given to Halter and Garske, recognizing that sacred music required more time and expertise than was often possible when the position was paired with a teaching one. Zion, Dallas, founded also by the Wends, was the mother church of the LCMS in North Texas. It had the resources for Gaertner to work out his vision. With this vision in mind, Zion issued a call to Donald Rotermund in 1955 to serve as “Minister of Music and Teacher,” the title “minister” suggesting a pastoral role, and that role receiving precedence over that of “teacher.” Gaertner hoped that Rotermund eventually could concentrate solely on music rather than on school teaching. The title “minister” was not without controversy in the region, but implied that Rotermund had an important role within the parish of proclaiming the Word.

Although it would be many years before Rotermund could be divested of non-musical teaching responsibilities to concentrate on parish music exclusively, the church was creative in allowing him time to advance his education (with a masters degree from then North Texas State University), much as Trinity, Houston, had done. In this environment, Zion’s music ministry flourished and became the center of Lutheran music in North Texas. Rotermund established the Dallas Lutheran Acapella Choir, which gathered choristers from local churches to rehearse and sing music of a scale not possible in their smaller choirs, often presenting their music in concert regionally. Paul Manz dedicated the new Schlicker organ in 1969, the first of that firm’s instruments in North Texas, after which the church became a center for local organ and choral concerts. Upon Gaertner’s retirement in 1976, Zion, Dallas, established what would become the Heritage Series, an award program that would formally recognize and express appreciation to certain individuals who had served the LCMS in parish music throughout the nation. This program resulted not only in increased appreciation for professional musicians throughout the LCMS, but resulted in numerous new choral and organ works commissioned for each event.

The career of Richard Leslie, another longtime Lutheran church musician in Texas, tells the story of another path toward full-time sacred music in Texas. Leslie, who graduated in 1970 from Missouri State University, majoring in organ performance and choral conducting, served LCMS churches in Michigan and Illinois before accepting a call in as director of Christian education in 1986 to Gloria Dei Lutheran Church in the Houston suburb of Nassau Bay, where his job originally involved overseeing adult education and all facets of a growing music ministry. The Church Growth Movement of the 1980s had influenced the church’s pastor, Rev. John Kieschnick, who, according to Leslie, believed that growing churches should employ less liturgical and traditional forms of ritual. Yet this same movement had also encouraged senior pastors to value their musicians—indeed, all of their staff—in a professional and ministerial sense, in much the same way as Rev. Gaertner had envisioned for his called musician at Zion, Dallas. Thus, early in his tenure at Gloria Dei, Leslie had not only completed colloquy in the LCMS; he had been relieved of DCE responsibilities in order to become its first “Minister of Music and Celebration,” allowing him to focus solely on parish music. Leslie remembered that “John Kieschnick insisted that his staff were part of his ministry. The spiritual authority of those working on staff was an outgrowth of his authority as senior pastor. In this way, he was convinced the church would grow. However, this meant he put his staff to work! The Minister of Music [and Celebration] would be the first ministerial contact for music people.”

Motivated by the example of the increasingly professional church music programs throughout the state, the Texas District of the LCMS began to notice the vocational parish musician, now an important subset of the pastoral and teaching callings. Rotermund, Garske, Rutz, and Gastler were at the forefront in teaching and presenting workshops for Texas musicians for years, but what had been a rather informal network of Lutheran musicians up until this time would become the Texas District Worship Committee after a district president had inquired whether the group would coordinate worship services for district conventions. By the time the committee disbanded in the 1990s, it had provided for decades a forum for pastors and musicians to study the history and practice of church music together, certainly inspiring conversations in their home church. Zion would continue to take leadership when, in the 1990s during the pastorate of Rev. Robert Preece, the idea for the Lutheran Hymn Festival at the Meyerson would originate with the church leaders. This hymn festival has brought organists to lead a mass choir and instruments on the CB Fisk Opus 100 organ at the symphony center.

Where do we stand today?

The health of a church is not determined by the number of its full-time, staff, musical or otherwise. The spiritual health of a church is determined by its adherence to Word and Sacrament; yet, especially in sacred music, some of the best and most thankless work is executed tirelessly every week by volunteers or part-time staff. During the 1980s in Texas, Harold Rutz remembered that there were very few full-time parish music positions; no doubt a similar observation could be made of the rest of the LCMS. Yet, between then and now, the number of full-time positions has grown to several dozen. What does this indicate? Hopefully it means more churches have the resources–and the consequent political will–to invest time, energy, and talent into their music programs. Of course, there are other ways to do this than by hiring staff, but this sort of research always seeks tangible metrics to bolster its conclusions, for better or for worse. Texas Lutheran clergy and musicians have encountered manifold challenges throughout the last 168 years, but they have always responded to them with creativity and have always acknowledge the utmost importance of congregational music. Whether drought or flood, lack of building space, or a pandemic, the sacred music of Texas Lutherans demonstrates a resiliency and faithfulness to the Gospel which should inspire future generations.